22 August 2025

The first Women's Rugby World Cup could easily not have occurred. The International Rugby Board refused to recognise the tournament, 600 potential sponsors were consulted with not a single one interested in supporting the event, and a number of unions refused sponsorship for their national women's teams, who then had to pay their own way. In spite of the odds, the women persevered and the participating nations came together in Wales from 6-14 April 1991 to show the world that rugby was not exclusively a sport for men.

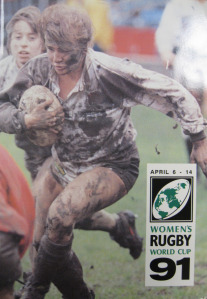

England's Gill Burns on the cover of the official tournament programme.

Twelve countries took part in the 1991 World Cup: USA, England, New Zealand, Netherlands, Canada, Spain, Wales, Sweden, Italy, Japan, the USSR and France (whom, despite being a haven for women's rugby, only joined the World Cup draw at the eleventh hour). A number of curious anecdotes came out of the tournament, one which concerns this late addition French team. Whilst we know for certain that the USA won the tournament and England placed second, there is a rather perplexing contradiction in the history books when it comes to who placed third. Officially, the place is shared between France and New Zealand. There was a game played between the two countries on the 14th of April; however, this match was not scheduled as part of the competition and does not appear in official tournament records. New Zealand does not acknowledge the game that they lost 3 - 0, but France has awarded caps for the match and claim the victory. What is a little clearer from the tournament is how the USA team's reputation and stature managed to intimidate a number of their opposition and spectators alike. Dubbed 'the Monsters from Hell', the Eagles team members were also labelled 'turbo props' and 'locks from hell'. Teammates included a qualified stuntwoman, Candi Orsini, and doctor Maryanne Sorensen who weighed in at a solid 13 stone. At the other end on the scale, the Japanese team included a number of petite women, including 4'9" tall scrum-half Ayako Horikita, who weighed in at a mere 7 stone. Unfortunately, Horikita saw only 10 minutes of play in Japan's first match against France before breaking her collar bone. The team carried on to lose 0-62 that day, performing a sporting bow every time a try was scored against them. Their sportsmanship was also demonstrated in their presentation of small gifts, such as origami, to their opponents at every game. Peculiarly, each member of the team played in a scrum-cap, regardless of their position, which baffled spectators.

New Zealand players attempt to win the ball from Wales' Liza Burgess.

The Kiwi women captivated audiences when they performed the Haka prior to their tournament matches. Special permission to perform the war dance was sought from Maori elders and was granted on the basis that it was afforded proper respect. Teammates Nino Sio and Elsie Paiti, however, were not granted permission from their respective South Seas leaders and had to watch from the side-lines. Despite refusing to fund the Gal Blacks, as they were then known, the New Zealand Rugby Football Union did allow the team to wear the silver fern synonymous with New Zealand Rugby on their jerseys for this tournament. Until this point, the fern had been restricted to male sides representing New Zealand. Likely the most fascinating story of all to come out of the 1991 Women's Rugby World Cup was the plight of the Soviet Union team. The women managed to make it to Wales, but only after failing to turn up on their original flight days earlier. When they finally arrived two days before the tournament was set to begin they had with them a number of 5-foot crates filled with goods for bartering - vodka, champagne and caviar. This was how the USSR women planned on paying for accommodation and food whilst in Wales. Indeed, they only brought with them enough cheese, sausage and brown bread to last 2 days and no cash, so this was their only hope. Upon being discovered and after a tough conversation with Customs and Excise officers, bartering their goods was no longer an option. Local people and business flooded the team with food, money and support, so that the women were comfortably able to remain in the competition. Whilst the Soviet women lost both games in their pool and scored 0 points, they were grateful for the experience. Team member Larisa Masalova recalled, "for most of us it was the first time we travelled abroad or even first time ever got travel passports. There was no target: just to get some experience versus great international teams." This was the only time that a USSR team had the opportunity to compete in the Women's World Cup. Political changes meant that by 1994 Russia and Kazakhstan were competing for the Women's Rugby World Cup in Scotland. Despite financial difficulties, the 1991 Women's Rugby World Cup was a resounding success and set a precedent for the growth of women's rugby. Sixteen years on, the game is now played by over 2 million women and girls worldwide and the Women's Rugby World Cup continues to provide a platform for inspiring further participation and engagement in women's rugby.