18 January 2026

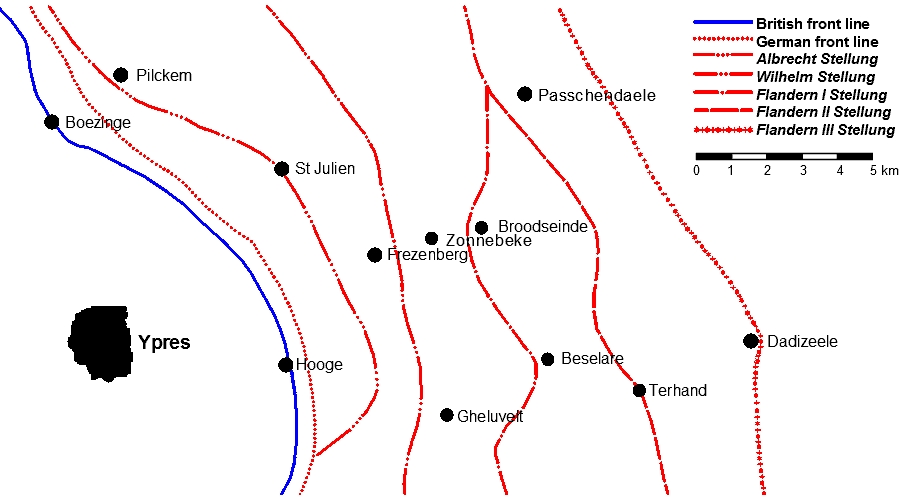

By capturing the village of Passchendaele, the British hoped to progress in the direction of the Belgian coast where the Allies might curtail the threat of the German U-boat. After long deliberation Prime Minister Lloyd George agreed Field Marshal Haig's plan and zero-hour was set for 3.50 am on the morning of the 31st July, after a fifteen-day four million shell bombardment. Lieutenant Colonel Mobbs had made his battalion headquarters inside a waterlogged trench in advance of Hill 60, where Fin Todd had been shot two years earlier. Further south Lieutenant Colonel Livesay and the New Zealand Division were forming up on the edge of the front line on the southern extremity of Messines Ridge.

The attack would commence in the dark to prevent German observation from the high ground. It was forecast to rain all day. The New Zealand Division made good progress, driving the Germans out of La Basse Ville and repelling a counter attack in the afternoon to hold the position. Mobbs' 24th Division however were less successful in their efforts to secure the strategically important, but waterlogged, Gheluvelt Plateau. Their difficulties were largely due to misfortune. Lower Star Post, a German pillbox stronghold, fell in between the lines of advance for two battalions. As a result both attempted to outflank it and came under heavy fire. The 7th Battalion Northamptonshire Regiment's problems were soon compounded as they became 'engulfed by heavy fire' from machine guns that had been brought forward from Jeer Trench.

As his men's predicament became apparent Mobbs had to be dissuaded from leaving his bunker. After restraining himself for another 30 minutes he could take no more and scaled the parapet with his second lieutenant. He suspected that a concealed machine gun must be preventing progress and so he went off in search of it. Sometime later he found it. He ordered his second lieutenant to approach from the opposite flank whilst he himself launched a frontal assault on the position with hand grenades. He was shot through the neck approximately 30 yards from the gun. Thinking only of his usefulness to the campaign he spent his last moments scribbling a note for Battalion HQ detailing the machine gun's exact position. His final scribbled words were 'Am seriously wounded'. Possibly no man was more emblematic of rugby's contribution to the First World War than Edgar Mobbs. His was a character that would have been as recognisable in rugby clubhouses of today as it was then. Though a natural leader of men, he was also modest and had refused his commission in 1914 in order to learn 'the rules of the game'. His irrepressible skill had seen him rise to a position of command just as his skills on the field had brought him to England colours. He had utter faith in his men and must have felt greatly responsible for them after so many had signed up to his self-raised battalion in 1914. Whilst his own ability and courage was demonstrated repeatedly between 1914 and 1917 he would not tolerate incompetence amongst his equals or superiors and had been reprimanded on more than one occasion on this count. Whilst under enemy fire an officious subaltern had pedantically insisted that his reports be written in conventional red ink. In a response that was typical of the man, Mobbs replied 'we are in the front-line trenches and have no red ink. There is, however, plenty of red blood here, so if you would like that instead, please instruct me to use it'. Edgar Roberts Mobbs is rightly revered in his native Northampton and the Mobbs Memorial Match takes place annually, in his honour, to this day.

Edgar Mobbs the Player

Edgar Roberts Mobbs was one of six children. His father was an engineer and his mother the daughter of a Northamptonshire shoe maker. Born in Northampton in 1882, he attended Bedford Modern School before embarking on a career in the burgeoning automobile industry. He had suffered a knee injury in his final year at school which prevented him from playing much sport and was a late bloomer as far as rugby was concerned, preferring mixed-hockey and only turning out sporadically for Olney Rugby Club in his early twenties. Over time he developed into a tall, strong centre or wing-three quarter with an awkward but effective running gait that proved very difficult for his opponents to counteract. By 1904 he was well known locally and was turning out regularly for Olney, Northampton Heathens and Western Turks. As he filled out physically he added an accursedly strong hand-off, kicking, throwing and try-scoring to his repertoire and during the 1905-6 season made his debut for Northampton Saints. It didn't take Mobbs long to put his stamp on the Saints and within two years he was club-captain. In 1908 he was selected to captain the combined Midlands and East Midlands Counties against Australia at Welford Road. His thrusting runs from deep set-up two tries and inflicted on the Wallabies their only defeat against an English side for the duration of the tour. His exploits were noticed by selectors and the following month he was selected for England to face the Wallabies at Twickenham. He made his debut alongside Francis Tarr and eight others under the captaincy of George Lyon and within three minutes of kick-off Tarr and Mobbs' intricate passing resulted in Edgar's first international try. He played in every round of the 1909 season and landed further tries against Ireland and Scotland. In 1910 he captained England against France and helped England to a first outright championship since 1892. In 1912 he played the first of several games for the Barbarians. In 1913 at the age of 30 he hung up his boots for Northampton Saints after captaining the side for six years and having amassed a total of 234 caps and 179 tries. He fell in 1917. He never married and his body was never found. He is remembered on the Menin Gate and has his own personal memorial in Abingdon Square, Northampton. His name is recorded on memorials at Olney, Northampton and Franklin's Gardens and there is a road called 'Edgar Mobbs Way' in Northampton.

About the Author: This article is an extract from the book 'Doing their Duty: How England's Rugby Players Helped Win the First World War'. Phil McGowan has been a member of the World Rugby Museum team since 2007.